DANIEL MARSHALL ARCHITECTS

- in progress

- 2012-2014

- 2009-2011

- 2007-2008

- 2006

- 2005

- 2001-2004

Concrete Utopia

Article by Daniel Marshall

Published in ArchitectureNZ, issue 4, 2009. Pages 30-31.

Concrete Utopia

Since I was an architectural student, the images and virtuoso freeform planning of Oscar Niemeyer have captured my imagination and I was determined to one day go to Brazil.

Earlier this year, I landed in Sao Paulo in the early evening on a Sunday. I was over-awed by the scale of the city, and the mass of humanity. The density created a tactile feeling of excitement. My first night in Brazil ended at dawn outside a club called Heaven, samba drums echoing in my head.

Later that day, somewhat the worse for wear, I walked to Ibirapuera Park. There, the work by Niemeyer – a collection of pavilions connected by a freeform pedestrian walkway within the park he designed – spanned 50 years from the first pavilions to the Auditorium, completed in 2005. As it turns out, the Niemeyer structures I had come to Brazil to experience were not at their best either. The passage of time had spooled the concrete and revealed the rudimentary qualities of the detailing. However, I was interested in the spatial qualities of the linking walkway in Ibirapuera Park. In a movie Niemeyer was interviewed walking through the space – he could have been in a carpark, and the low concrete roof looked oppressive. But it isn’t: the structural gymnastics eliminate most columns and the curvilinear forms and tapered structure lend a lightness to the edges that absorb the fecund green surroundings. It felt good to walk along there. The low roof provides vital shade and keeps the tropical rainfalls at bay, providing a space for people to perambulate. On weekends the walkway is full of people.

In Ibirapuera Park I saw my first Niemeyer dome, the Lucas Nogueira Garcez Pavilion (1954). I was always a little sceptical about the domes, but there is a cultural precedent in Brazil: the oca (or ‘hut’), a traditional Indian structure covered in leaves. I ate lunch at the Kilo restaurant, a buffet where they weigh the food, in the centre of the walkway.

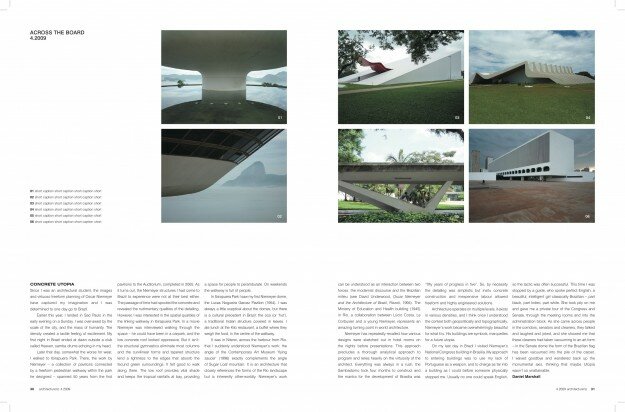

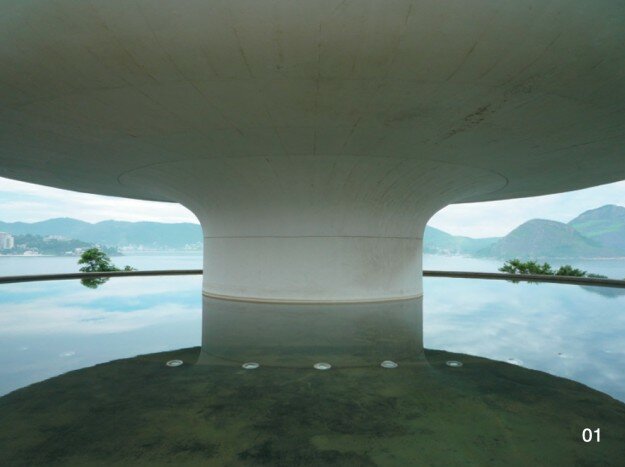

It was in Niteroi, across the harbour from Rio, that I suddenly understood Niemeyer’s work: the angle of the Contemporary Art Museum ‘flying saucer’ (1996) exactly complements the angle of Sugar Loaf mountain. It is an architecture that closely references the forms of the Rio landscape but is inherently other-worldly. Niemeyer’s work can be understood as an interaction between two forces: the modernist discourse and the Brazilian milieu (see David Underwood, Oscar Niemeyer and the Architecture of Brazil, Rizzoli, 1994). The Ministry of Education and Health building (1945) in Rio, a collaboration between Lúcio Costa, Le Corbusier and a young Niemeyer, represents an amazing turning point in world architecture.

Niemeyer has repeatedly recalled how various designs were sketched out in hotel rooms on the nights before presentations. This approach precludes a thorough analytical approach to program and relies heavily on the virtuosity of the architect. Everything was always in a rush, the Sambadomo took four months to construct and the mantra for the development of Brasilia was “fifty years of progress in five”. So, by necessity the detailing was simplistic but insitu concrete construction and inexpensive labour allowed freeform and highly engineered solutions.

Architecture operates on multiple levels, it exists in various densities, and I think once I understood the context both geopolitically and topographically, Niemeyer’s work became overwhelmingly beautiful for what it is. His buildings are symbols, marquettes for a future utopia.

On my last day in Brazil I visited Niemeyer’s National Congress building in Brasilia. My approach to entering buildings was to use my lack of Portuguese as a weapon, and to charge as far into a building as I could before someone physically stopped me. Usually no one could speak English, so the tactic was often successful. This time I was stopped by a guide, who spoke perfect English, a beautiful, intelligent girl classically Brazilian – part black, part Indeo, part white. She took pity on me and gave me a private tour of the Congress and Senate, through the meeting rooms and into the administration block. As she came across people in the corridors, senators and cleaners, they talked and laughed and joked, and she showed me that these cleaners had taken vacuuming to an art form – in the Senate dome the form of the Brazilian flag has been vacuumed into the pile of the carpet. I waved goodbye and wandered back up the monumental axis, thinking that maybe Utopia wasn’t so unattainable.

Daniel Marshall

Next Blog Post: Speak Easy, ArtSpace, KRd

Previous Blog Post: Korora published in HOME New Zealand